The Silk Road, a network of trade routes connecting the East and West, stands as one of the most significant achievements in human history. Far more than just a means of exchanging goods, this ancient highway became a conduit for the transmission of ideas, technologies, religions, and cultures across vast distances. Stretching over 4,000 miles from China to the Mediterranean, the Silk Road flourished for nearly two millennia, shaping the development of civilizations along its path and leaving an indelible mark on world history.

The term “Silk Road” was coined in 1877 by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen, but the routes had been in use for thousands of years prior. The network began to take shape during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) when China officially opened trade with the West. While silk was indeed a major commodity, giving the route its romantic name, a vast array of goods traversed these paths, including spices, textiles, precious stones, metals, ceramics, glass, and even slaves.

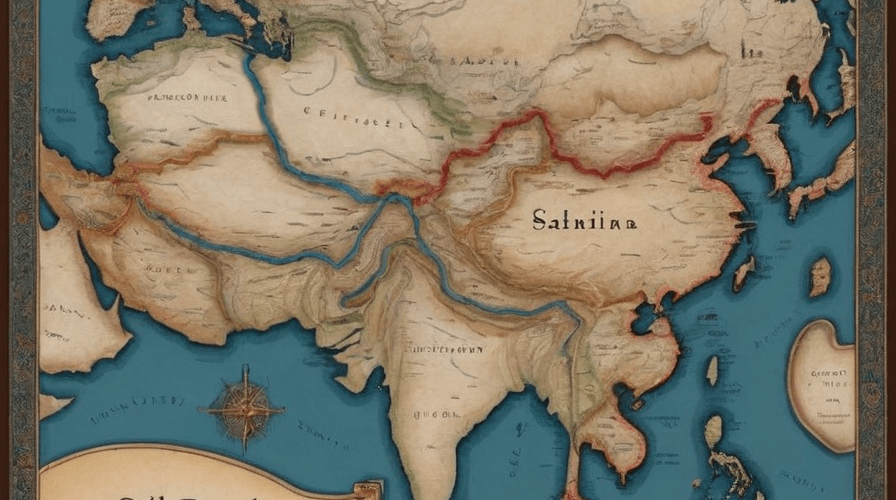

Contrary to popular belief, the Silk Road was not a single, well-defined route but rather a complex network of paths that shifted over time due to changing political alliances, environmental conditions, and bandit activity. The main arteries ran from Xi’an in China, through Central Asia, and on to the Middle East and the Mediterranean, with numerous branches and offshoots along the way.

One of the most significant impacts of the Silk Road was its role in the spread of religions. Buddhism traveled from India to China along these routes, profoundly influencing Chinese culture. Similarly, Christianity, Islam, and Zoroastrianism spread across Central Asia via the Silk Road. This exchange of religious ideas led to unique syncretic practices and the development of new schools of thought.

The Silk Road also facilitated the exchange of technologies and innovations. Paper-making, invented in China, spread westward along the routes, revolutionizing record-keeping and the dissemination of knowledge in the Middle East and Europe. Gunpowder, another Chinese invention, traveled west, dramatically changing warfare. In return, China received new crops like grapes and alfalfa, as well as new concepts in art and music from the West.

Languages and writing systems also mingled along the Silk Road. The Sogdian language, spoken by merchants from Central Asia, became a lingua franca for trade. The spread of alphabetic writing systems influenced the development of new scripts in various regions. This linguistic exchange facilitated communication across vast distances and diverse cultures.

The movement of people along the Silk Road led to significant genetic and cultural mixing. Recent genetic studies have revealed the extent of this intermixing, with populations along the route showing diverse genetic heritage. This movement of people also led to the exchange of agricultural practices, cuisines, and artistic styles.

Major cities along the Silk Road became melting pots of culture and commerce. Places like Samarkand, Bukhara, and Chang’an (modern Xi’an) grew into cosmopolitan centers where merchants, scholars, and pilgrims from different parts of the world congregated. These cities became hubs of learning and cultural exchange, often housing important libraries, observatories, and centers of scholarship.

The Silk Road also played a crucial role in the development of diplomatic relations between distant empires. The Han Dynasty of China and the Roman Empire, while never directly in contact, were aware of each other through the intermediaries along the Silk Road. This indirect contact influenced their perceptions of the world and their place in it.

However, the Silk Road was not without its dangers. Bandits, harsh desert conditions, and political instability made travel perilous. Merchants often banded together in large caravans for protection. Caravanserais, fortified way stations, were built along the routes to provide shelter, supplies, and security for travelers.

The exchange of goods and ideas along the Silk Road also had unintended consequences. Diseases, including the bubonic plague, are believed to have spread along these trade routes, leading to devastating pandemics. The Black Death of the 14th century, which decimated populations across Eurasia, is thought to have originated in Central Asia and spread along the Silk Road.

The importance of the Silk Road began to decline in the 15th century with the rise of maritime trade routes. The Age of Exploration saw European powers establishing sea routes to Asia, gradually rendering the overland Silk Road less crucial for long-distance trade. However, the legacy of the Silk Road lived on in the cultures, languages, and genetic makeup of the populations along its path.

In recent years, there has been renewed interest in the concept of the Silk Road. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, announced in 2013, aims to revive and expand the ancient trade routes, connecting Asia, Europe, and Africa through a network of infrastructure projects. This modern incarnation of the Silk Road reflects the enduring appeal of connecting distant regions through trade and cultural exchange.

The Silk Road’s impact on world history is immeasurable. It facilitated the first truly global exchange of goods and ideas, connecting disparate civilizations and fostering a level of cultural interaction unprecedented in human history. The routes served as a crucible for technological innovation, religious diffusion, and artistic cross-pollination.

Today, the UNESCO Silk Road Project works to preserve the cultural heritage of the Silk Road, recognizing its importance in shaping our modern world. Archaeological sites, ancient cities, and cultural practices along the route continue to provide insights into this remarkable period of human history.

In conclusion, the Silk Road stands as a testament to the power of human connection and the transformative nature of cultural exchange. For nearly two millennia, it served as the world’s central nervous system, transmitting goods, ideas, and innovations across vast distances. The legacy of the Silk Road reminds us that globalization is not a modern phenomenon but a process that has been shaping human civilization for thousands of years. As we face the challenges and opportunities of our increasingly interconnected world, the lessons of the Silk Road – the benefits of open exchange and the richness that comes from cultural diversity – remain as relevant as ever.

Add comment